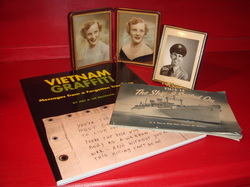

A few of years ago, my dad, Richard Klamm, had my stepmother Arlene email me a link to a story about a book that he had recently purchased called “Vietnam Graffiti: Messages from a Forgotten Troopship” by Art and Lee Beltrone. I was a bit confused since dad served in Korea, not Vietnam, which, of course, was the intent of the email because he knew I’d call and ask.

As it turns out, the book is about a military ship, the U.S.N.S. Gen. Nelson M. Walker, which was used for a scene in the movie “The Thin Red Line” starring such notables as Sean Penn, Adrien Brody, George Clooney, John Cusack and Woody Harrelson. The discarded ship had been anchored along with others in Virginia’s James River. The book itself is an excellent pictorial history of the ship and its focus is on all the graffiti left by Vietnam era soldiers on the underside of the canvas bunks. Poetry, drawings, letters and reminiscences cover the fabric undersides of the cots chronicling a separate yet collective history of the men transported on board this ship. I still failed to see the connection to my dad, but eventually he cleared up the mystery.

Although the N.M. Walker was built during WWII and the book is a telling of its Vietnam years, it just happens to be the ship Dad was stationed on when he went to Korea after he was drafted in 1952. And although he was in the Air Force, his two ocean crossings (there and back) were aboard this particular troopship.

Not surprisingly, Dad didn’t talk much about the time he spent in Korea and this was the first I’d heard of the N.M. Walker voyages. If it hadn’t been for a book published by a writer of which I’d never heard, Dad may never have said a word about it.

Dad graduated from Washington High School in Kansas City, KS in 1950. Like many families in the neighborhood at the time, the Klamms did what they could to eek out a living. So the following year, when Dad made the decision to buy a brand new bullet-nosed Studebaker Champion, the thrifty one for ‘51, it was a big deal.

He got a loan from a local insurance agent for the car, but no sooner than the ink dried on the paper, Dad received “Greetings from the Government” in the form of an invitation to join the Korean War effort, in other words, a draft notice for the Army.

Deciding he wanted to have a little control over his destiny, he opted to join the Air Force instead. So one day, he took the Army physical and the next day, he took the Air Force version. He then headed off to communications school, which would soon be followed by an all expenses paid trip to Korea.

But what to do with the car? Unfortunately, his new military wages weren’t going to cover the payments on his beloved Stude. With his hat in his hands, he went back to Cliff Dosier, the agent who loaned him the money, and explained the situation. Cliff, being the stand-up kind of guy he was, told Dad not to worry about it. They’d just refinance the car and he didn’t have to worry about the payments until he got back.

After training at Scott Air Force Base in Illinois, Dad was sent overseas in January 1954. The ship landed at Yokohama and he and the other soldiers were sent by train to Tachikawa AFB, which is located approximately 40 miles northeast of Tokyo.

That first night, dad and the other soldiers who made the trip alongside him slept in tent He said it was the coldest night he has ever experienced in his life.

From Tachikawa, Dad was sent to an AFB in Kunsan located near Seoul, Korea.

He arrived in Korea about six months after the armistice, which was signed on July 27, 1953. So, although he never saw any combat, he was still ill at ease being stationed in a country of such great unrest. He lived in a barracks that was located in a metal Quonset hut and as a communications specialist, it was his job to run up to the top of a hill every morning and night to be sure the communication tower and equipment was working properly.

“We supplied radio and telephone communications to the ROK [Republic of Korea] training base,” he told me.

The barracks was serviced by a houseboy dad referred to as Skosh, although I have no idea how the name is really spelled. Skosh gave dad a picture of himself holding a severed head. He explained it was the head of his friend and in order to get enough ammunition to protect his family, he had to kill his friend and bring back proof to the South Korean government. That proof was his friend’s head. I can only imagine how this added to dad’s uneasiness.

Dad’s stint in Korea was over in December 1954 and he crossed back to the United States once again on the N. M. Walker. He spent the remainder of his time in the Air Force stationed at Fort Walton Beach in Florida and was discharged on October 6, 1956, the same day my older brother was born. In fact, Dad had to get a special pass to get back on base to pick up my mom, my sister and my brother as he was now a civilian.

Dad kept the Studebaker until late 1957/early 1958, when he lost his mind and traded it for a Plymouth. He turned 77 this year and I’ll bet he’d give his right eye tooth to have that car back – me too. But I’m feeling pretty lucky that the publication of a book I may never have read had he not pointed it out lead me to such rich family stories about my dad.

As it turns out, the book is about a military ship, the U.S.N.S. Gen. Nelson M. Walker, which was used for a scene in the movie “The Thin Red Line” starring such notables as Sean Penn, Adrien Brody, George Clooney, John Cusack and Woody Harrelson. The discarded ship had been anchored along with others in Virginia’s James River. The book itself is an excellent pictorial history of the ship and its focus is on all the graffiti left by Vietnam era soldiers on the underside of the canvas bunks. Poetry, drawings, letters and reminiscences cover the fabric undersides of the cots chronicling a separate yet collective history of the men transported on board this ship. I still failed to see the connection to my dad, but eventually he cleared up the mystery.

Although the N.M. Walker was built during WWII and the book is a telling of its Vietnam years, it just happens to be the ship Dad was stationed on when he went to Korea after he was drafted in 1952. And although he was in the Air Force, his two ocean crossings (there and back) were aboard this particular troopship.

Not surprisingly, Dad didn’t talk much about the time he spent in Korea and this was the first I’d heard of the N.M. Walker voyages. If it hadn’t been for a book published by a writer of which I’d never heard, Dad may never have said a word about it.

Dad graduated from Washington High School in Kansas City, KS in 1950. Like many families in the neighborhood at the time, the Klamms did what they could to eek out a living. So the following year, when Dad made the decision to buy a brand new bullet-nosed Studebaker Champion, the thrifty one for ‘51, it was a big deal.

He got a loan from a local insurance agent for the car, but no sooner than the ink dried on the paper, Dad received “Greetings from the Government” in the form of an invitation to join the Korean War effort, in other words, a draft notice for the Army.

Deciding he wanted to have a little control over his destiny, he opted to join the Air Force instead. So one day, he took the Army physical and the next day, he took the Air Force version. He then headed off to communications school, which would soon be followed by an all expenses paid trip to Korea.

But what to do with the car? Unfortunately, his new military wages weren’t going to cover the payments on his beloved Stude. With his hat in his hands, he went back to Cliff Dosier, the agent who loaned him the money, and explained the situation. Cliff, being the stand-up kind of guy he was, told Dad not to worry about it. They’d just refinance the car and he didn’t have to worry about the payments until he got back.

After training at Scott Air Force Base in Illinois, Dad was sent overseas in January 1954. The ship landed at Yokohama and he and the other soldiers were sent by train to Tachikawa AFB, which is located approximately 40 miles northeast of Tokyo.

That first night, dad and the other soldiers who made the trip alongside him slept in tent He said it was the coldest night he has ever experienced in his life.

From Tachikawa, Dad was sent to an AFB in Kunsan located near Seoul, Korea.

He arrived in Korea about six months after the armistice, which was signed on July 27, 1953. So, although he never saw any combat, he was still ill at ease being stationed in a country of such great unrest. He lived in a barracks that was located in a metal Quonset hut and as a communications specialist, it was his job to run up to the top of a hill every morning and night to be sure the communication tower and equipment was working properly.

“We supplied radio and telephone communications to the ROK [Republic of Korea] training base,” he told me.

The barracks was serviced by a houseboy dad referred to as Skosh, although I have no idea how the name is really spelled. Skosh gave dad a picture of himself holding a severed head. He explained it was the head of his friend and in order to get enough ammunition to protect his family, he had to kill his friend and bring back proof to the South Korean government. That proof was his friend’s head. I can only imagine how this added to dad’s uneasiness.

Dad’s stint in Korea was over in December 1954 and he crossed back to the United States once again on the N. M. Walker. He spent the remainder of his time in the Air Force stationed at Fort Walton Beach in Florida and was discharged on October 6, 1956, the same day my older brother was born. In fact, Dad had to get a special pass to get back on base to pick up my mom, my sister and my brother as he was now a civilian.

Dad kept the Studebaker until late 1957/early 1958, when he lost his mind and traded it for a Plymouth. He turned 77 this year and I’ll bet he’d give his right eye tooth to have that car back – me too. But I’m feeling pretty lucky that the publication of a book I may never have read had he not pointed it out lead me to such rich family stories about my dad.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed